Routers have become enormously popular for sharing broadband and even fast dial-up lines among two, three, or, in my family’s case, eight computers. Prices too low to ignore on 10/100-Mbps Ethernet adapters, hubs, and switches started the headlong rush, and plummeting hardware router prices have made the home LAN irresistible. A router, in my book, is vastly preferable to an always-on PC acting as a gateway. Although some broadband providers encourage routers and sharing, others expressly forbid it or don’t seem to care. But even where sharing is verboten, it’s like the old 55-mph speed limit: Everyone I know ignores the rule.

How Sharing Works

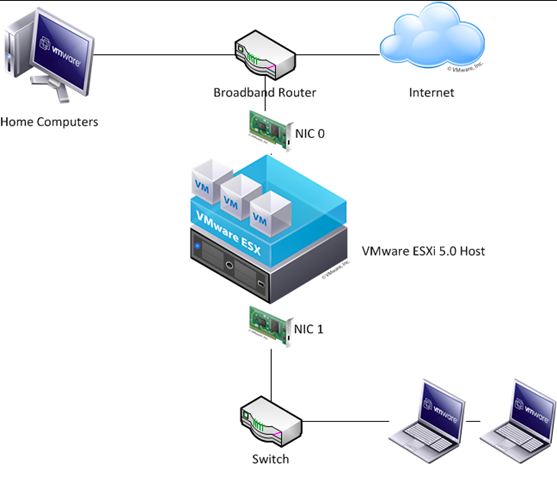

Internet connection sharing is accomplished by a clever bit of magic known as NAT. Every machine on a network has to have a unique IP address, and your ISP assigns you one—either permanently (static IP) or temporarily each time you connect (dynamic IP). Multiple machines behind your cable or DSL modem need separate addresses, or chaos would reign. You could request additional IP addresses from your ISP, but there are a couple of practical limitations: additional cost and a finite limit to the number of static addresses. So your router, strategically located between the modem and your PCs, tells your ISP that it is the only machine present. It then assigns an IP address, typically in the 192.168.xxx.xxx space, to each machine. Addresses in this range are nonroutable, which means they cannot pass through a router. They can be viewed by other machines behind the router, however.

Within each IP address, a packet of information can be addressed to any of 65,535 different ports, which are just software subaddresses. Some are predefined, such as port 80 (for HTTP traffic) and port 110 (for POP3 mail). Most of the thousands of others are undefined. Your router substitutes a port number for each machine’s nonroutable IP address and appends it to your assigned IP address, so that it can route reply packets to the right machine, a process sometimes called “opening a tunnel.”

You’ve no doubt heard that a PC exposed to the Internet shouldn’t have any ports open (software acting as a server of one kind or another), because they can act as an entry point for hackers. A router, by nature, doesn’t have any ports to open, so it’s impervious to port probes. And no probe can find those machines with nonroutable addresses, right? Not necessarily.

The techniques are too complex for me to describe here, but it’s possible to hack NAT. And if the truth be told, NAT isn’t all that smart: A series of rogue packets could follow a tunnel that’s just been opened to one of your PCs, and a bad packet that sufficiently resembles a good one can be passed through. And none of NAT’s machinations defend you from viruses, Trojan horses, or zombie programs that take over your machine and open a big hole, letting what looks like legitimate traffic pass through your router. To be truly safe, you should run antivirus and firewall software on each machine behind your router. Firewall software also prevents supposedly trusted machines from probing your LAN. I’ve logged attempts from my coworkers.

Too Much Faith

Do people put too much faith in NAT? I recently ran a poll at www.extremetech.com to find out. Roughly 25 percent of those who responded said they trust NAT; 40 percent said they don’t and also run firewall software. 10 percent run routers with stateful packet inspection, and 15 percent don’t do anything special but say they’ve never been hacked. The remainder don’t know whether they’re secure or not.

To those who say you’ve never been hacked: How do you know? Your machine could be zombied at this very moment. Stateful packet inspection is a good defense against some kinds of attacks but still does nothing to prevent viruses or Trojans. It can’t protect you from hacks coming from local machines. And a compromised machine behind the router has the potential to give up your machine.

Router vendors are aware of the unwarranted faith that some users place in NAT, and some now recommend and even bundle firewalls. Take heed.